Come Tomorrow

Nina Sudhakar

| Fiction

Hello, aunty, Diya said. The woman had introduced herself as Amrita but Diya couldn’t bring herself to use a first name on a woman of her age.

You again, Amrita said, but there was a hint of a smile on her face. More photographs?

I didn’t bring anything this time, sorry. I just couldn’t stop thinking about this place.

Strange, Amrita said. Most try not to think about this place at all. For good reason.

Why— Diya began, but Amrita interrupted.

No more biscuits, I’m afraid, but I just made some bajjis, if you want some.

She left the door ajar, and the wind slammed it shut suddenly with a loud bang, startling them both. Amrita looked over nervously at the neighboring house. Diya followed her gaze and noticed two heads quickly ducking back into the doorway, trying in vain not to be seen.

So there are other people here, Diya said. Do you want to invite them to join us?

They won’t come, Amrita said. She looked again at the neighbor’s house and back at Diya. But I can ask.

She walked over and was gone for some time. Diya drew semicircles with the toe of her sneaker in the dust. When Amrita came back, she was followed by a crowd, mostly men and women of similar ages, white-haired, with no children or younger adults in sight.

There were others who’d seen you here, Amrita said. They wanted to know who you were. I told them about the photograph you gave me. I wanted to show them.

Inside her house, Amrita had propped the photo up on a teak chair in the courtyard. It sat there like one of the house’s inhabitants: the house itself, or its exterior; how it appeared to others.

Diya stood a short distance away with Amrita while the crowd took turns examining the photograph. After, a man in a stiff button-down and dress pants approached her.

I don’t have any photographs of my house, not like this, he said. It’s been in my family for generations. Do you think you could photograph my house, too?

Diya agreed, and other residents approached her to make similar requests. She rented a scooter and found herself going back and forth on that same city-to-village stretch many times over the next several months, drinking Limca or tea or water on the neighbors’ porches, eating an assortment of snacks offered to her, and periodically remembering her camera, raising it only when the moment felt right, which resulted not from her knowledge of proper lighting or ideal composition but a nudge somewhere below her ribs that told her now, now, NOW.

After a time, some residents began asking for portraits of themselves, which Diya took, too, coming back each time laden with prints, the once-identical houses becoming irrevocably distinct because of the people she now knew to live within each of them.

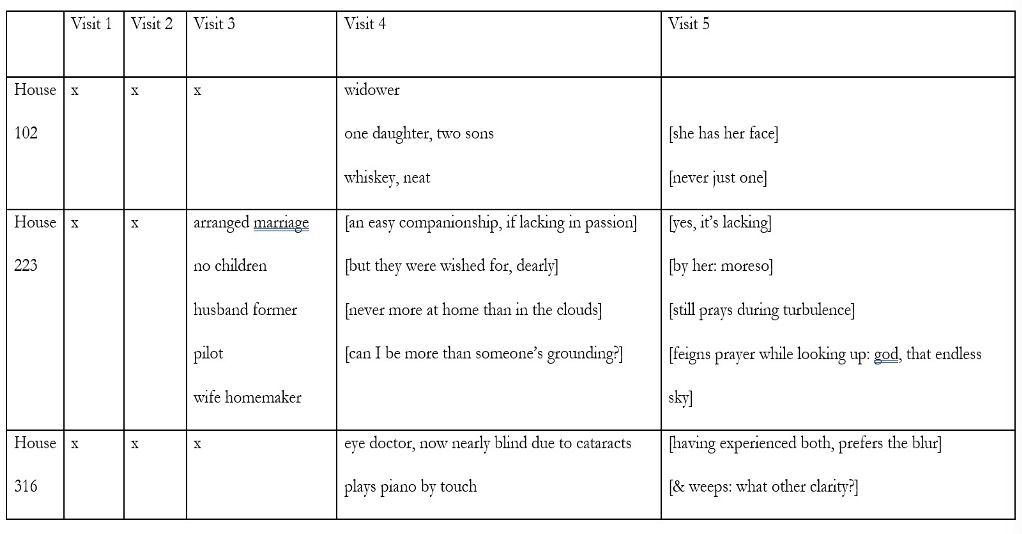

For instance:

On one visit, when Diya wrapped up her day at Amrita’s, she finally decided to ask.

Oh yes, the writing above the doorways, Amrita said. It means “come tomorrow,” you see, to ward off the stranger.

*

Nina Sudhakar is a writer, poet, and lawyer based in Chicago. She is the author of the poetry chapbooks Matriarchetypes (Bird’s Thumb, 2018) and Embodiments (Sutra Press, 2019) and her work has appeared in The Rumpus, Witness, Ecotone, The Offing, and elsewhere.